Kirsten Fulgham

Past Graduate Student

-

ENR2

1064 E Lowell St

Tucson, AZ 85719

Assessing Dipodomys spp. foraging response in proximity to a colony of reintroduced black-tailed prairie dogs

As part of the larger guild of burrowing herbivorous rodents, Dipodomys spp. are considered to be an important keystone guild whose role as ecosystem engineers and habitat modifiers complements that of Cynomys spp. Together these genera organize and structure arid grassland ecosystems and the biodiversity therein by providing a mosaic of microhabitat patches and increasing overall heterogeneity(Heske et al. 1993; Guo 1996; Fields et al. 1999; Brock and Kelt 2004; Davidson and Lightfoot 2006, 2007, 2008; Kelt 2011). Kangaroo rats are considered ecosystem engineers due to their foraging methods, mound building, burrowing, and nutrient cycling activities (Hawkins and Nicoletto 1992; Longland 1995; Guo 1996; Davidson and Lightfoot 2006). They fulfill the role of keystone guild by having a large-scale influence on vegetative composition and diversity as well as the species dominance structure of various patch types in desert grasslands (Brown and Heske 1990; Heske et al. 1993; Fields et al. 1999). Both granivory and graminivory of kangaroo rats likely factor into their keystone status (Kerley et al. 1997)

Within the grasslands of southeast Arizona, the burrowing granivorous rodent guild is composed primarily of banner-tailed kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spectabilis), Merriam’s kangaroo rats (Dipodomys

merriami), and Ord’s kangaroo rats (Dipodomys ordii) (Hoffmeister 1986; Hale, personal comm). However, since the 1960’s a significant component of the guild, the prairie dog, has been absent (Arizona Game and Fish Department 2013). Historically, this area was in the range of the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus). Reintroduction efforts began at the Las Cienegas National Conservation Area in October 2008 and continue today with the goals of increasing ecosystem health, biodiversity, and the rangeland conditions (Bureau of Land Management 2003; Underwood and Van Pelt 2008).

My study examines the indirect effects that black-tailed prairie dogs might have on resident kangaroo rats in an area of reintroduction. I will use the methodology of Giving-up Density (GUD) to assess these effects.

Research Questions: Is there a difference in the perceived quality of foraging habitat by kangaroo rats when comparing outside to inside a prairie dog colony in different seasons as measured by GUD?

I predict that the perceived difference in habitat qualities inside and outside a prairie dog colony at different seasons will significantly affect the GUD of foraging kangaroo rats.

- In summer and fall when natural food resources are higher outside the colony than inside, there will be higher GUDs outside the colony than inside.

- In summer and fall when natural food resources are higher outside the colony than inside there will be a greater difference between GUDs inside versus outside the colony.

- In winter and early spring when natural food resources are low both inside and outside the colony, there will be higher GUDs inside the colony than outside.

- In winter and early spring when natural food resources are low both inside and outside the colony, there will be a lesser difference between GUDs inside versus outside the colony.

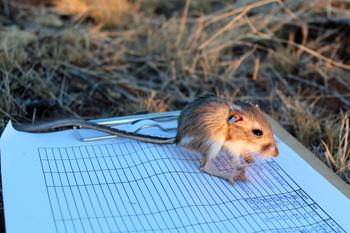

Watch a kangaroo rat foraging on on a seed tray used to assess giving up density